Is Lifting Heavy Essential For Muscle Growth?

Feb 20, 2018 mindpumpMuscle size and strength are often synonymous. Most bodybuilders are quite strong, and most of those who are strong are also quite big. But does correlation equal causation? By this I mean, is getting strong and lifting heavy HOW those who are big got to be that size? The answer is YES and NO.

When programming for muscle size, volume is key. Volume is the primary driver of hypertrophy, not intensity or load. Lifting heavy all the time will likely not lead to a great deal of muscle hypertrophy (growth). But occasionally programming cycles focused on increasing your strength can aid in increasing volume over time by allowing you to move more weight for more reps on all of your lifts. This is just a basic summation of a much greater concept. Lifting heavy absolutely has a place in a well-designed hypertrophy program, and actually, so does lifting with lower loads and higher reps – they all have a place.

Lifting heavy (repetitions performed at above 85-90% of 1RM) primarily adapts the CNS and motor units, not necessarily the skeletal muscle fiber itself. Growth of the fiber is known as myofibril hypertrophy, something that usually occurs when small structures within the muscle cell known as myofilaments have time to repeatedly cross one another, thus causing micro-tears. These small tears lead to the re-growth of larger fibers, thus creating hypertrophy within the muscle cells fibrous components. This is where heavier lifting fails. Generally lifts performed at higher loads are not performed with enough repetitions, or long enough eccentric contractions to adequately stimulate cross bridge formation, and therefore that oh so valuable cross-bridge formation is missed. Before you throw lifting heavy out the window, hear me out. If You remember from earlier, volume is the number one driver of hypertrophy – but it is not the only driver. In his landmark review of hypertrophy and what causes it “THE MECHANISMS OF MUSCLE HYPERTROPHY AND THEIR APPLICATION TO RESISTANCE TRAINING,” Brad Schoenfeld identifies the THREE primary physiological drivers of muscle growth:

1. Mechanical Tension:

More easily described as time under tension, is a mechanism by which the bodies muscle fibers undergo a great deal of active stress. Think about controlling a set of dumbbell bench press for 12 reps and allowing for two seconds at each phase of contraction (eccentric, isometric, and concentric) that amounts to over one minute under tension. This stress leads to a tremendous amount of both structural change (at the muscle fiber) and environmental change (within the muscle cell body’s non fiber compartments) that create a very favorable environment for growth.

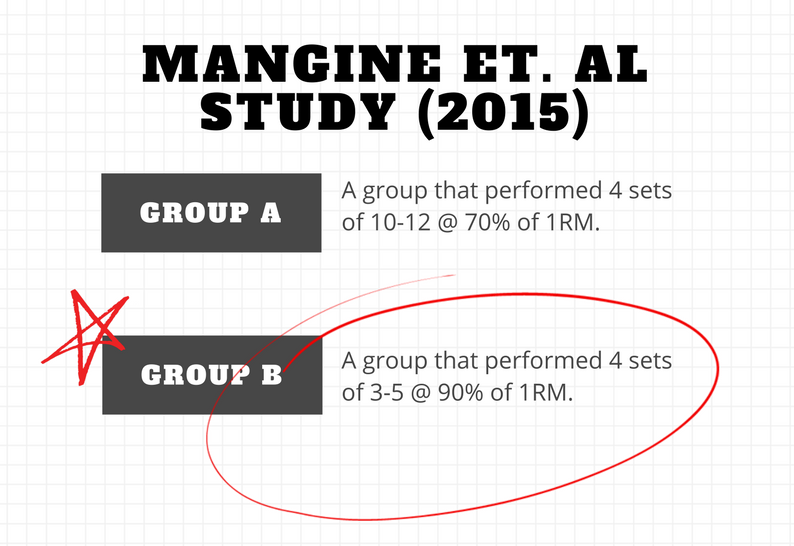

2. Muscle Damage: This is where lifting heavy and training to failure come into play. While neither of the above mentioned mechanisms are NECCESARY, Schoenfeld ‘s finding do support that muscle damage (generally occurring under greater loads) can lead to hypertrophy. In addition to Schoenfeld’s findings, a study by Mangine Et. al in 2015 compared 33 physically active men into two groups:

Interestingly, Group B gained both more strength AND more muscle. While one could argue that the groups may not have been well trained, it stands to reason to include high-intensity work in a hypertrophy program.

3. Metabolic Stress:

This mechanism of hypertrophy focuses on what is called “sarcoplasmic hypertrophy”. Sarcoplasmic hypertrophy is the growth of the muscle cells non-fibrous parts and is driven by the buildup of anabolic metabolites within the muscle cell. Things like occlusion training, and low-load, high rep training are good examples of training styles that drive the metabolic stress adaptation of hypertrophy. While recent research supports that this is an ample mechanism for hypertrophy, it should be part of a greater overarching program.

The consensus in the scientific community is that a long-term increase in volume, calculated as (sets x reps x weight) will elicit the greatest results as it pertains to muscle growth.. Lifting heavy and getting stronger will allow for greater increases in volume as well as provide a variation in training stimuli and create an environment where muscle damage can readily occur.

In conclusion, If you are looking to get big, it makes sense to also get strong. Only lifting heavy (high intensity, low volume) over time will not likely yield the best gains, but phasing in and incorporating periods of deliberate strength gains and CNS power adaptations will definitely improve your ability to increase volume over time. The increased volume coupled with manipulating and progressing exercises, loads, tempo-schemes, and other variables that allow you to dabble in all three of the hypertrophic mechanisms will undoubtedly lead to some impressive gains.

Author: Daniel Matranga

NASM: CPT, CES, PES, WLS, SFS, WFS, GFS, YES

ACE: TES, OES, and MBS

Mangine, Gerald T, et al. “The Effect of Training Volume and Intensity on Improvements in Muscular Strength and Size in Resistance-Trained Men.” Physiological Reports, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Aug. 2015, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4562558/.

Schoenfeld, Brad. “The Mechanisms of Muscle Hypertrophy and Their Application… : The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research.” LWW, The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, Oct. 2010